Picturing What It Means To Be Free

In Bob Adelman’s photograph of Martin Luther King, Jr., Martin Berger observes how

“the civil rights leader strikes a powerful pose as he gestures toward the sky against the colossal columns of the Lincoln Memorial behind him. But the speech immortalized by the photograph was lauded in the 1960s (and is popularly revered today) for its recollection of a ‘dream.’ In the snippets of the address most commonly recalled by whites, King does not remake the world but simply dreams of a more perfect order to come” (Seeing Through Race, 2011, 28).

Ernest Withers’s photograph of the sanitation strike in Memphis in 1968 is similarly well known today. It is often interpreted as an imagined future. It records Black workers’ mass walkout in February 1968 and their infamous placards that read “I AM A MAN” in protest against discriminatory treatment and life-threatening working conditions. With their disparate clothing and physiques, the men were united by their race and their declaration of shared identity – as men.

The "I'm a Man" mural (2015) is designed by rap artist Marcellous Lovelace in a modern graffiti style and installed by BLK75. It depicts sanitation workers assembling in front of Clayborn Temple for a solidarity march, Memphis, Tennessee, March 28, 1968. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In his reading of Withers’s image, Berger notes further that

“The poignant assertion of humanity (and manhood) invokes the inscription on the antislavery medallion designed by Josiah Wedgwood in 1787, which he in turn modeled after the seal of the English Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade of that year (32).

Am I Not a Man and a Brother? 1787. Tinted stoneware medallion designed by Josiah Wedgwood. 3.2 x 3.2 cm. Library of Congress.

Am I Not a Man and a Brother? 1787 medallion designed by Josiah Wedgwood for the British anti-slavery campaign on 1 January 1795, The Official Medallion of the British Anti-Slavery Society.

Wedgwood’s inscribed enslaved Black man asks, on bended knee, “Am I not a man and a brother?” an imagery that was a ubiquitous visual representation of emancipation in the nascent United States that tugged at the emotions of white abolitionists during and immediately after the US Civil War.

Hammatt Billings’ scenes of Uncle Tom and little Eva in the arbor in Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)

In my book, Uncle: Race, Nostalgia the Politics of Loyalty I explain how Harriet Beecher Stowe (and the novel’s American illustrator, Hammatt Billings) depict Uncle Tom as a man in the prime of his life: dark haired and broad shouldered, which was a typical depiction of Black men before the Civil War.

As Jo-Ann Morgan writes in Uncle Tom as Visual Culture (2007),

“Before emancipation, a few other dark-haired, broad-shouldered Black men had appeared in print. Images of one escaped slave, holding a rifle and standing tall, was inspiring propaganda to justify the war for Northern readers of Harper’s Weekly” (31).

The abolition of slavery only intensified the problem of how to represent Black men in the visual culture. Once abolished, slavery retreated to the domain of memory. There, those collective memories had to be reckoned with in one way or another: suppressed, integrated, or romanticized. Emancipation, in effect, moved four million formerly enslaved African Americans, with their history of enslavement, into the national memory.

“The Escaped Slave in the Union Army,” Harper’s Weekly, July 2, 1864, p. 428. House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections

All Black bodies, by extension, ceased to exist in the present nor were they imagined in the future; instead, to be Black meant to be past tense, to belong to the collective memory. It is not a coincidence that the Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Park, Washington, D.C., erected in 1876 mirrors a past headpiece illustration by Hammatt Billings in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Uncle Tom's Cabin: Illustrated Edition (1853) depicts a Christian belief in kneeling to God. In the novel, two White characters are shown kneeling, while the enslaved are frequently on their knees.

Emancipation Memorial in Lincoln Park (1876). Archer Alexander is the real-life model for the newly freed enslaved in this monument also called the Freedman’s Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Appearing on the title page for chapter thirty-eight of the second edition of the novel, these almost identical images reinforce the narrative of gratitude which was proscribed onto enslaved people. The Emancipation Memorial depicts President Abraham Lincoln — the man who “freed” the slaves — standing over a kneeling and shirtless Archer Alexander, a formerly enslaved African American. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin image, Jesus stands in the place of Lincoln, Uncle Tom in the place of Alexander.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., leading a group of civil rights activists seeking the right to vote in prayer on Feb. 1, 1965 in Selma, Alabama after they were arrested on charges of parading without a permit. Getty Images

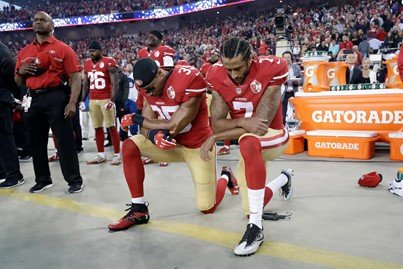

Colin Kaepernick takes a knee at an NFL game in protest against anti-Black racism, 2017. Marcio Jose Sanchez, Associated Press.

Photographer Clay Banks. Source: Unsplash

To have hope you have to dare to question the things you have taken as essential truths. Where many folks read the image of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in 1965, Colin Kaepernick in 2017, and Black Lives Matter protesters in 2020, as depicting the act of kneeling in protest to systemic racism and against systems of capital that have benefited from Black servitude and disenfranchisement, others see anti-heroes, unpatriotic rebel rousers, and non-citizens who are not “grateful” for all that they have been given.

If there is one takeaway from this essay, it’s to ask why the iconography of kneeling Black people keeps reappearing in Western visual culture. What do they signify? Why do they keep returning? If the social conditions of our time are different from the 1960s — and the 1860s — why does the quest for freedom and its associated kneeling iconography still appear today as it did centuries ago? When will people of African heritage truly be free?

In my opinion, when we ask this question, we are not asking the right question. Instead, we need to start asking how we can reframe the very notion of freedom that is not in response to, or in conversation with, White structures of domination. What does freedom look like when not tethered to Western capitalist structures of seeing and feeling? In the 21st century, when we begin to ask different sets of questions, the iconography of Black people kneeling — whether in servitude or in protest — will begin to disappear from the zeitgeist so that we can co-create a new (and future-centred) iconography of Black freedom.

A version of this essay was originally presented at Intersections Cross-Sections Graduate Conference & Art Exhibition, York University and Toronto Metropolitan University in 2021.